James Powell & Sons were not only Britain’s longest running glass house they were the most productive, innovative and in my opinion, by far the best. Their glass always reflected the fashion of the day and in many cases actually made the fashion possible in the first place, through their development of new technologies and processes and their inspired designs. The factory of Whitefriars, largely forgotten until recent years is now enjoying a huge revival, collectors and museums worldwide are taking a serious new look at the glass of James Powell & Sons

Although having advertised as 300 Years of Glass making. Records actually date back to 1720, for a small glassworks off Fleet Street, London.

The factory really came into its own when James Powell a London wine merchant and entrepreneur, purchased the factory in 1834, the idea was to give his three sons a viable occupation. The Powell’s were related to Baden Powell, the Scout Movement founder.

The Powell’s were initially ignorant of the art of glass making, but by necessity soon acquired the skills needed and adapted and improved upon the new technologies of the industrial revolution. A large portion of their production during this early period was the manufacture of church stained glass windows, they invented and patented processes of manufacturing, the sections of glass or “quarries” this innovation set them up as leaders in the field when hundreds of new Victorian churches were being built across the country and indeed the world.

During the later portion of the 19th century the Powell’s became closely associated with leading architects and designers notably T G Jackson, Edward Burne Jones, William De Morgan and James Doyle. Not to mention Philip Webb that designed glass for William Morris and was manufactured by Whitefriars. By the late 1850’s the firm’s attention now begins to include designs and production of domestic table glass after manufacturing glass for William Morris’s revolutionary

In 1875 Harry James Powell, the Grandson of the founder joined the factory. Harry an Oxford graduate, having specialized in chemistry. His approach to glass making was somewhat more scientifically based. He was responsible for many new innovations in glass technology, new colours from chemical processes and new techniques. Notably the development of heat resistant scientific glass, for use in laboratories and industry, and for the likes of x-ray tubes and early light bulbs.

Harry’s fascination with developing new forms of glass such as opalescent glass moved the company to new heights of late Victorian fashion. Interestingly there is a Straw Opal vase set in the foundations of Tower Bridge. They exhibited in almost every major exhibition around the world. A large portion of the tableware produced was inspired by historical glass, Venetian, Roman and copied from oil paintings in Europe’s museums and art galleries. He was also somewhat of a socialite and was involved with many organizations and movements. Harry a follower of Ruskin regularly lectured on glass and glass technology at major industrial seminars.

The factory’s designs moved with fashion which at this time was the new Art Nouveau style, During this period the factory produced some of their most stunning glass. They were by now earning their place as world leaders in the field of quality glassware.

In 1919 James Powell & Sons changed its name to Powell & Sons (Whitefriars) Ltd and plans were made for a new factory, This was to be a large state of the art building with every modern facility and technique available. In 1923 the furnaces were lit in Wealdstone near Harrow West London, using a flame taken from one of the furnaces in Fleet St and carefully moved to Harrow in a brazier (a metal pan containing burning coals).

Business was good but the vast expenditure of building the factory and plans to build a “Garden suburb” style housing village for the workers, (The Powell’s were heavily influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement who’s ethos was to produce top quality hand made crafts, and to give the skilled craftsmen good pay and good accommodation). But the pressure of the village had put great financial strain on the business. Reluctantly they decided to scrap the housing development and concentrate on glass manufacture.

Production in the new factory was about half domestic and half scientific glass utilizing the work and experiments James Powell had pioneered on heat resistant glass, glass tubing and new colours in the previous few decades.

Between the wars period was a very productive and creative time for the factory and their financial situation had improved.

New glassware became more colourful and in many cases heavier. Optic molding and the dramatic use of wheel engraving in geometric designs reflecting the “Art Deco” style, that was the fashion, indeed the upper and middle classes that were the core customers were enjoying the Roaring Twenties.

This halcyon period was about to come to an abrupt end with the onset of World War II. Glass production continued was strictly limited to essential glass only, as dictated by the government as part of the war effort.

After the war the company struggled to return to its pre-war prosperity, rationing which continued until the early fifties and fires at the factory all contributed to a gloomy outlook. Some of the factory’s key skilled craftsmen had enlisted into to the armed forces, and many of those had not returned.

The Festival of Britain came in 1951 and happier times for the factory, indeed the whole country benefited from this attempt to re-start the economy and manufacturing industries. Whitefriars was chosen as one of the businesses to represent modern British industry, live glass blowing demonstrations were provided for a war wary public. As always Whitefriars embraced the new styles of the time, and the 50’s style was no exception. This was largely inspired by the new atomic age. Indeed the splitting of the atom had a profound effect on design in general in the Western World.

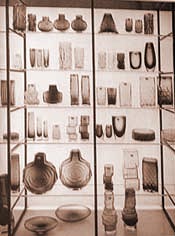

The remaining years of the decade saw the Scandinavian style which was sweeping Europe, the clean lines and sophisticated designs found approval with major retailers such as Selfridges and Fortnum & Masons. Another important development was the invention of slab glass or concrete glass, a new form of stained glass window. Thick slabs of coloured glass were set in concrete making a kind of mosaic, which proved popular with churches, schools and public buildings as they reflected perfectly the 1950’s look.

During the mid 1960’s the designer Geoffrey Baxter who had joined the factory in 1954 directly from the Royal School of Art, began experimenting with a completely new approach to glass design, the idea was to create a completely new style of glass suitable for the swinging sixties,a “groovy baby” style, the hallucinogenic sixties had arrived.

Ply-wood, nails, pieces of bark, bits of wire, and all manner of materials were used to create prototype moulds. The moulds were re-made in more durable cast iron. They had to be made in 3 parts due to the complexity of the designs. The same moulds were usually used for the entirety of the production run, so by looking at how defined the texture on the piece is, its possible to estimate how early the example. Due to the fact that moulds wear with age. However the temperature of the mould at the time of blowing also has an effect on the crispness of the finished piece, i.e. glass flows more readily into a hot mould.

This new glass was to become known as the Textured range, and was released in 1967 initially in three colours, cinnamon, indigo, and willow. More colours such as tangerine (a new colour developed by Whitefriars) and blue were added two years later, mainly from demand by retailers. In 1963 the factory changed it’s name to “Whitefriars Glass Ltd” and re-designed its logo to the stylized monk at the top of this page.

Also released in the late sixties were the Studio Ranges, these were designed by the likes of Peter Wheeler, a young designer at the factory. Produced only for a couple of years as they were expensive and difficult to manufacture. These were the only examples of Whitefriars that were regularly signed. (They had whitefriars and the date engraved on the base)

The factory sadly hit hard times during the next decade, mainly because their parent company Zeal’s, switched orders for industrial tubing to the American owned Corning. Whitefriars made their tubing by hand and could not compete with Corning’s machine made counterpart. Tubing had represented about a quarter of the overall gross production so this had a very damaging effect on the fortunes of the company.

The old thermometer drawing tower, used to pull out tubes for clinical thermometers by gravity was made redundant by, the invention of the digital thermometer. So it was converted to draw millefiori canes for use in high quality paperweights which became increasingly popular during this period. Especially for the Queens Silver Jubilee in 1977.

Whitefriars continued to make textured domestic glass, notably the new Glacier range of 1972, limited edition paperweights and traditional cut glass, for the rest of the seventies, but sadly the stained glass studio closed in 1973 due to lack of demand.

The sad but inevitable end came in 1980 when the factory closed, Interest rates, high fuel costs plus the fact Britain was in the tight grip of a recession had all played their part in the demise of the factory. The furnaces were extinguished, staff laid off and factory was quickly demolished to make room for new developments. The records and contents of their museum were given to the Museum of London, (where they can still be viewed by appointment). The trademark “Whitefriars” was purchased by the Scottish glass maker Caithness, which they still use today as part of their paperweight range.

Geoffrey Baxter sadly died in 1995 but its heart warming to know that before he died the momentum had already begun for his glass to gain it’s now cult status. His glass had become collectible and he was well aware of the historical importance of his designs before he died.

Whitefriars glass has over the last fifteen years had somewhat of a revival especially the textured ranges by Geoffrey Baxter which have increased in price tenfold.

As for the earlier pieces, they too are becoming extremely collectible and more difficult to find, but I think they are yet still to achieve the status they truly deserve .